“THE coroner has to establish three things,” Michael Oakley tells me. “Who the person was, why they died and the circumstances of how they came to their death. It’s a fact-finding mission entirely. What people don’t realise - I think even more so today - is that it’s not a court of blame.”

Mr Oakley, who turns 75 this year, is retiring as coroner for the North Yorkshire East area - encompassing Scarborough and Ryedale - after 40 years in the job.

Over those four decades he has performed inquests in cases that merit investigation, for example sudden deaths, unexplained deaths, or deaths at work.

I tell him that I imagine there are many who have read newspaper reports from inquests, or have even attended them in some capacity, and still not fully understand the coroner’s place in publicly recording the who, how, when and where of someone’s death.

“The role of the coroner is really part of the registration of death procedure,” he says.

“It may well provide evidence for people to take subsequent civil proceedings, but that’s as may be. It does not blame anyone.”

He pauses, and then provides something of a qualifier, referring, for example, to complex medical scenarios: “It may ‘point the finger’ in acute cases, but it’s very seldom that you can find gross negligence - and it obviously has to be gross to point the finger.”

Mr Oakley became coroner for the area in the autumn of 1979. Prior to that, he was a solicitor in private practice, a position he maintained alongside the part-time coroner post until 1996.

After that, he sat as a judge both on the appeals tribunal and on the immigration tribunal in London, and for some years performed those roles in addition to being coroner, until around three years ago.

His last day as coroner will be March 29.

Death is a difficult subject; difficult to confront, to deal with, to talk and write about. But death is central to the role of the coroner. Over his career he must have dealt with thousands of bereaved and bereft families. I wonder if that is hard emotionally.

“Yes, I think it’s always difficult. You have to empathise with the people before you. You are always emotionally detached, but you have to recognise their emotions.

“The most hardy appearing person who comes to give evidence in a very straightforward way can often suddenly break down in the court room, and you have to allow for that fact. One tries to press on, allowing time for them to compose themselves, and in the main they do.

“But you have to recognise you’re dealing with the bereaved. It’s often months after the event, but for them, everything suddenly rolls back to when the death took place.”

I wonder if, as a society, are we any good at dealing with death. “I think society is to a large extent,” Mr Oakley says. “They bend over to try to support the bereaved, in many circumstances. I just cite, for an example, that the police have family liaison officers, who hold the hand of bereaved people arising out of those matters where the police have been involved. Road traffic accidents, and worse.”

But in those cases where public bodies such as police aren’t involved, Mr Oakley suggests there is something of a gap - particularly when it comes to legal matters. “People are dealing with this problem that’s come into their lives without any assistance as such,” he says. “The assistance they can get, I’m afraid, is limited by money. That brings me onto the issue of whether society recognises that people who appear at complicated inquests really require representation?”

At the moment, he says, families attending complex inquests rarely have legal help - and he sees this as a problem, though those complex inquests themselves are rare.

“I don’t think that assists the family and it certainly doesn’t assist the coroner,” he says. “A litigant, as they are, is emotionally involved, and is probably the worst position to be in. One would welcome a representation for people - so to that extent and for those sorts of inquests, society doesn’t provide all the help it could.”

The coroner records conclusions in the cases of people who have died in an enormous range of circumstances. These can be put into a number of categories, from suicide and accidental death to ‘misadventure’.

Over 40 years in the role, I wonder if he has seen trends or changes in how people are dying. It’s a grisly subject, but I’m interested, so I ask.

“The big trend is drug deaths,” he says. “People taking cocktails of drugs and probably have no intention of dying but they take the drugs and then die. There’s a definite increase in those sorts of deaths.

“If you take suicide, there used to be, in my experience, quite a lot of carbon monoxide deaths. I think those have reduced. But my recent experience has been that hangings have increased. So we’ve knocked out one and they use another method.”

The work of the coroner can have far-reaching effects - on public life and even on law. Recommendations made by a coroner can lead to real action.

In Ryedale, of course, the safety of the A64 and its various junctions is a huge issue in the district. Mr Oakley has often tried to highlight points along the road for improvements - and advocates the dualling of the road between York and Scarborough.

“I remember the Easingwold bypass when it was opened,” he says. “It had a roundabout at its southern end but at the northern end there was no roundabout at all. And there was very serious collision there. Recommendations were made and actually the roundabout was built very soon afterwards. I could never understand why it hadn’t been built in the first place.”

And it’s not just road deaths. “There was another case I had a number of years ago in Scarborough when there was a building in multiple occupation. A child and an adult died in a fire. And there were a lot of complications arising out of the fact that these people were effectively locked into the property because of bad housing regulations. That actually led - some 15 years later - to those regulations being changed in a Housing Act.

“So one saw good coming out of that - but it all takes a long time.”

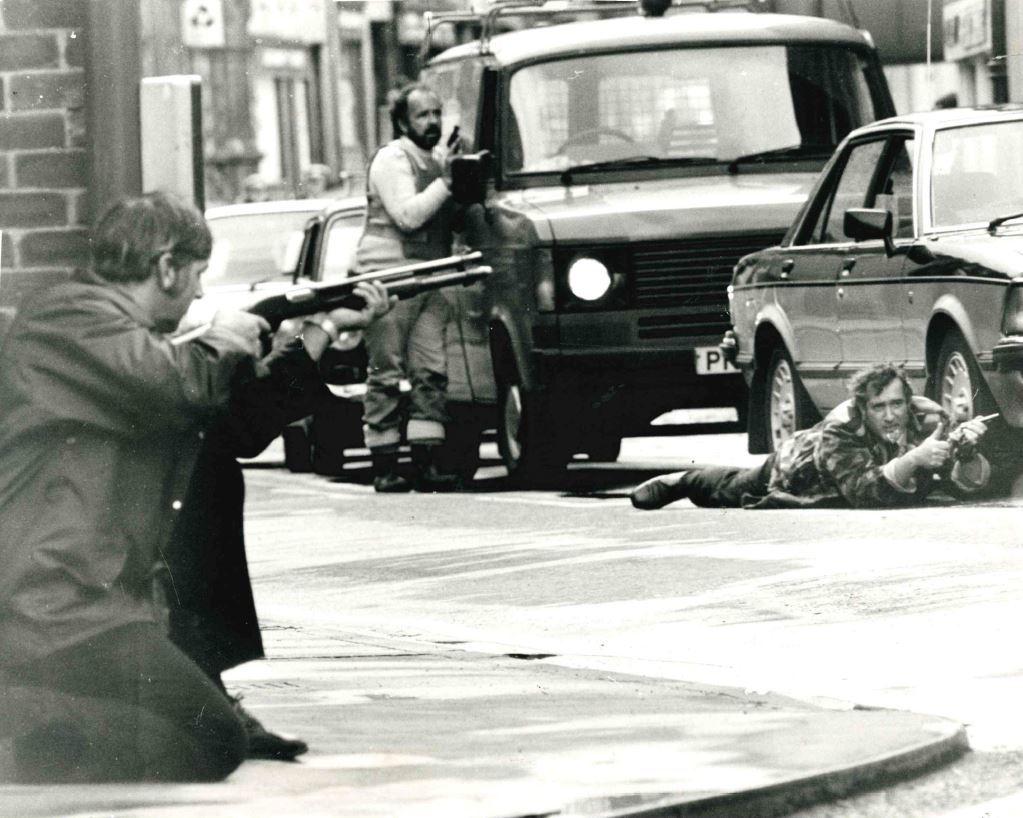

He has presided over some notable cases. In 1982, just a few years into the job, he was coroner in an inquest which drew national and international attention: the inquest into the suicide of the gunman and police killer Barry Prudom following ‘the siege of Malton’.

“There was big manhunt all round Malton and he was eventually cornered near the tennis club in Malton and he shot himself,” he remembers. “It certainly put Malton on the map at the time.”

Prudom became the subject of a police manhunt and what was, at the time, the largest armed police operation the country had ever seen.

He killed two policemen and a civilian over a six week period in the summer of 1982, before turning the gun on himself.

Following Mr Oakley’s inquest, the jury took only 18 minutes to return a verdict of suicide.

What does the future hold for the coroners’ service? Mr Oakley has advocated for many years that the whole of North Yorkshire - and possibly York too - should be amalgamated into one service. It could be based centrally, he said, perhaps in Northallerton. “The magistrates’ court is closing and there’s been talk about taking that over. Northallerton is actually quite a good place, in terms and road and rail, to serve the county.

“What there would hopefully be there is a dedicated coroners’ court. One of the difficulties I’ve experienced over the last 10 or 15 years is getting a place to hold inquests. We have to recognise it’s not just one room. You need a room for witnesses, you need a room for representatives, and in jury cases you need a room for jurors.

“We sometimes end up needing about five rooms - certainly for longer inquests. And there just aren’t those facilities available.”

As a reporter I have attended inquests in town halls, village halls, rugby clubs, business parks, council offices and a room above a cafe. One popular location is a particular rugby club near Scarborough.

“That’s quite reasonable to get to and everything,” he says, “but it wasn’t the best because you had noises going on next door, and people waiting just had to sit in the passageway.

“The final straw was when I was doing an inquest and a lady was giving evidence and she was fairly emotional. She’d just stopped saying whatever she was saying and there was applause next door - the timing was terrible. I thought, ‘No, we can’t have this’.”

New venues may be found and the structure of the coroners’ service in North Yorkshire may change, but whatever happens, the retirement of Mr Oakley really is the end of an era.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here