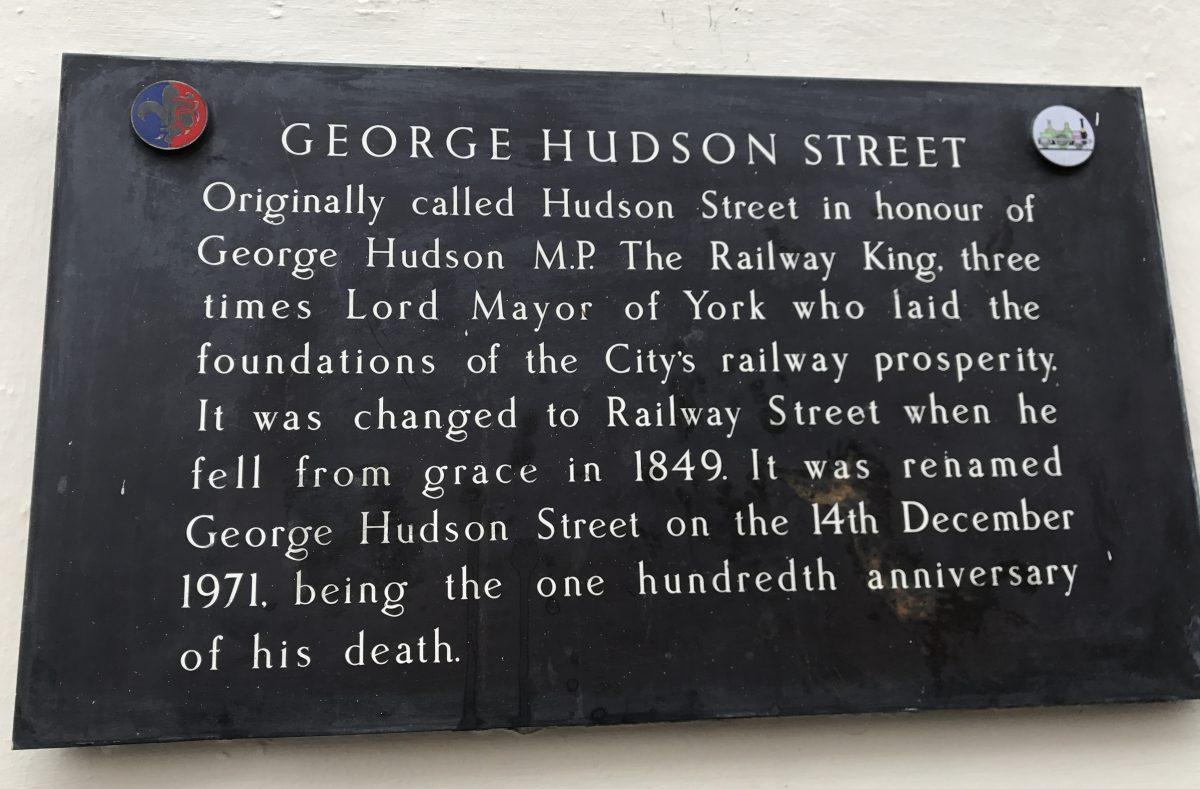

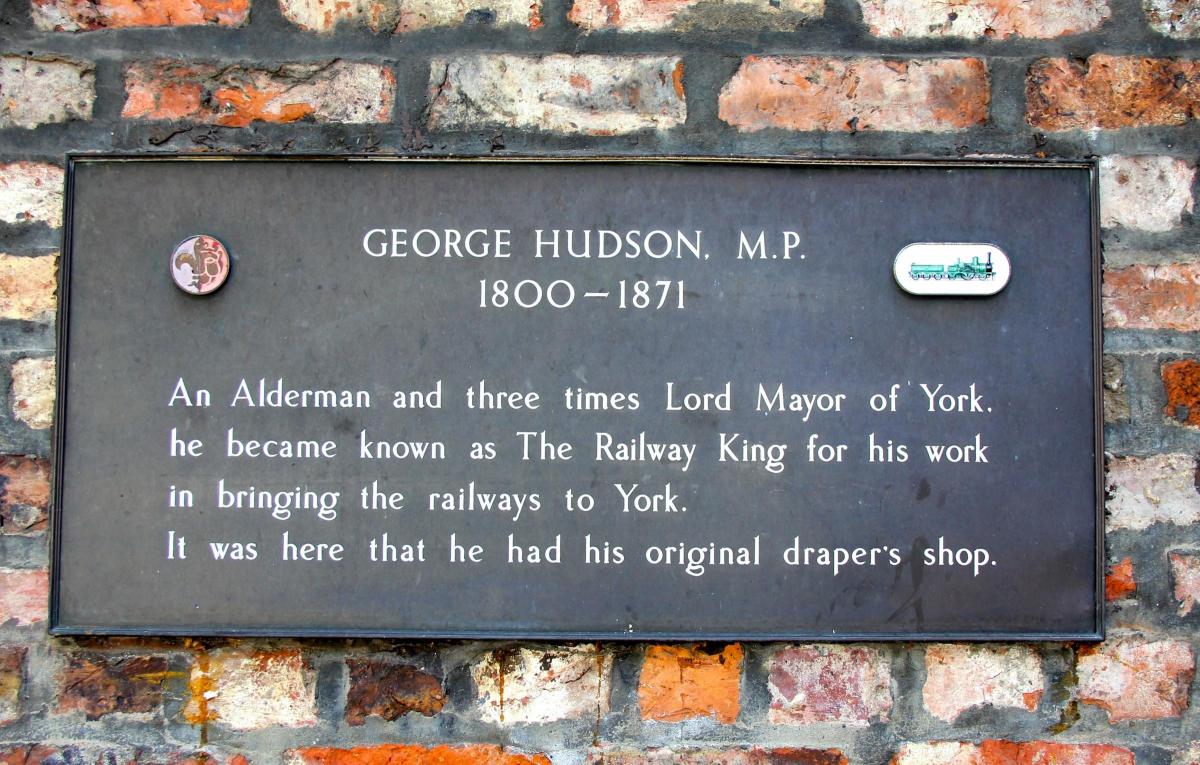

York Civic Trust Plaques

George Hudson (1800 – 1871)

'The Railway King'

Location of plaques in Hudson Street, College Street and Monkgate.

SOME people are just greedy. Not content with one plaque in his honour, George Hudson has managed to amass three. But then, he was a larger than life character.

Hudson was born on March 10, 1800, at Howsham near York, the fifth son of farmer John Hudson. His parents died when he was young and he was brought up by older brothers until, at the age of 14 or 15, he was sent to York as apprentice at drapers Bell & Nicholson.

Hudson completed his apprenticeship in 1820 and, in 1821, married Nicholson’s daughter, Elizabeth, and was given a share in the company. When Bell retired, Hudson replaced him.

As a partner in York’s most successful business, Hudson was already a wealthy man when, in 1827, he inherited £5,000 from his great-uncle, Matthew Bottrill. Now one of the richest men in York he moved into his great-uncle’s Georgian townhouse in Monkgate. He became treasurer of the local Tory party, played a leading part in the establishment of the York Union Banking Company and, in 1833 joined a scheme planning a York to Leeds railway.

In 1835 he was elected councillor for Monk Ward; the following year he became an alderman and then Lord Mayor of York in 1837.

In 1839 Hudson became Lord Mayor again in time for the opening of his railway between York and Leeds. He had also gained control of eight small rail companies to form the Darlington to York line.

By 1844 Hudson controlled more than 1,000 miles of railway. He was elected MP for Sunderland in 1945, a seat he held until 1859.

In 1845 York Corporation debated a proposal for a London to York railway. Hudson opposed it because it would undercut his own lines. However, he did support other projects to benefit York. On his election as Lord Mayor for a third time in 1846, he persuaded the council to build Lendal Bridge, now a vital part of the city’s transport infrastructure.

In the mid-nineteenth century the Government became concerned about railway speculation. Irregular financial manipulation, often involving electoral bribery and illegal share dealing, was common. Hudson became caught up in this.

Unable to stop the direct London to York route being built, he tried to put together a parallel line by extending the Eastern Counties Railway but this was uncompetitive. Dividends and share prices in railway stock were falling but, ignoring the reality, Hudson continued to buy or lease new routes. He began to pay dividends out of share capital and, as a last resort, sold his own shares and also land he did not own. Committees of enquiry were set up and he was called to appear before Parliament. As a sitting MP, he could not be prosecuted for debt. But he was forced to relinquish all of his chairmanships, sold most of his assets to pay debts, and was still forced to flee to France to escape creditors. He lost the Sunderland parliamentary seat in 1859 and lived abroad until he was tempted back to stand for Whitby in 1865. A few days before the election, he was arrested for fraud, tried in York and served three months in prison. When released, he lived for the rest of his life with his wife in Pimlico, where he died in 1871.

Hudson’s biographer, Robert Beaumont, says while The Railway King's financial practices were dubious, his legacy was Britain’s great rail network, which he created almost single-handedly.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel