UP on the moors, December is not the most vibrant month of the year. Much of the spring and summer colour has faded; that luminous lilac blooming of the heather is a distant memory and other heathland plants like yellow tormentil, blue milkwort and pink lousewort have also finished flowering.

There is still colourful interest, though, you just have to search a little for it. In areas where heather has been recently burnt or mown, down at ground level you may come across pale blue/green stalks, no more than an inch or two tall.

Some, at their apex, sport a blob of intense scarlet giving them the appearance of strange, otherworldly matchsticks.

They are of course lichens, or more specifically, a species called Cladonia floerkeana. Not surprisingly, country names for them include Bengal matchsticks and matchstalk lichen.

There are other types of lichen on our local moors, some like Cladonia grow on the peaty soil, some on rocks and others on heather stalks or tree branches. We don’t tend to notice them because they are small, dull and very slow growing.

For such unassuming organisms though, they boast an incredible biology. Lichens are not actually one creature but two.

The structural part of their body is a fungus, but internally they possess cells of an algae which are able to photosynthesise and make food for the team. Essentially they are a seaweed inside a mushroom.

This symbiotic relationship evolved so long ago that each team member is now utterly dependent on the other – they cannot live separately anymore.

As a group lichens can live almost anywhere but individually they are incredibly fussy. One species will only live on rocks on the sea shore, one only on the northern side of veteran oak trees and another on lime-rich cement.

This fussiness has led to Britain having an incredible 1,300 different lichen species because we boast such a wide variety of substrates and habitats. Some scientists rate our country, for its size, as the best place in the world for lichens.

Before you get too excited, we do have scores of lichens in Ryedale but it is the west of Britain where the spectacular diversity is to be found, not because it’s warm and wet but because of human pollution. Almost all lichens are very sensitive to sulphur dioxide pollution in the atmosphere.

Atlantic winds hitting the west coast are free of this gas but by the time they get across to us on the east coast they have picked up significant quantities of SO2 from industry and car fumes. Things have improved since the days of coal fires and many of our local lichens are thriving again and brightening up our flower-free winter days.

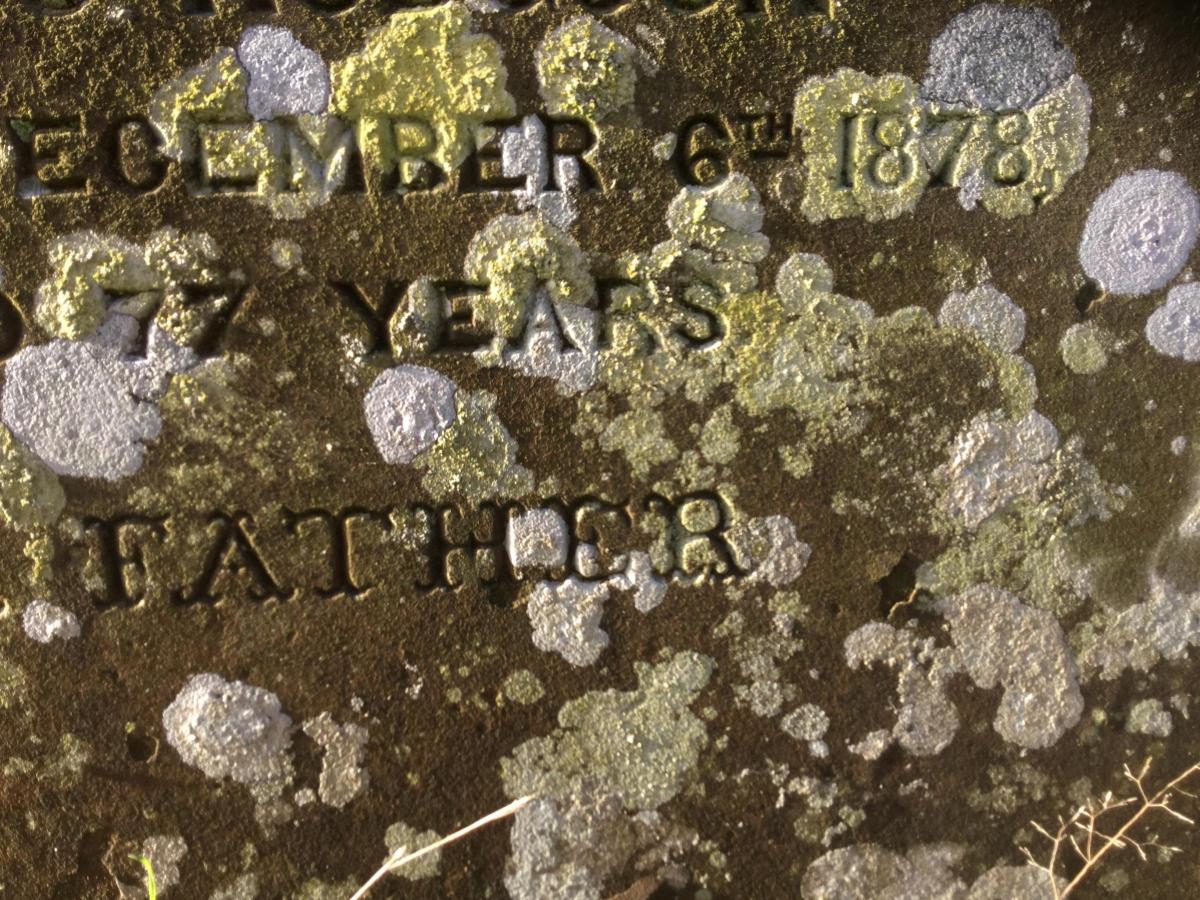

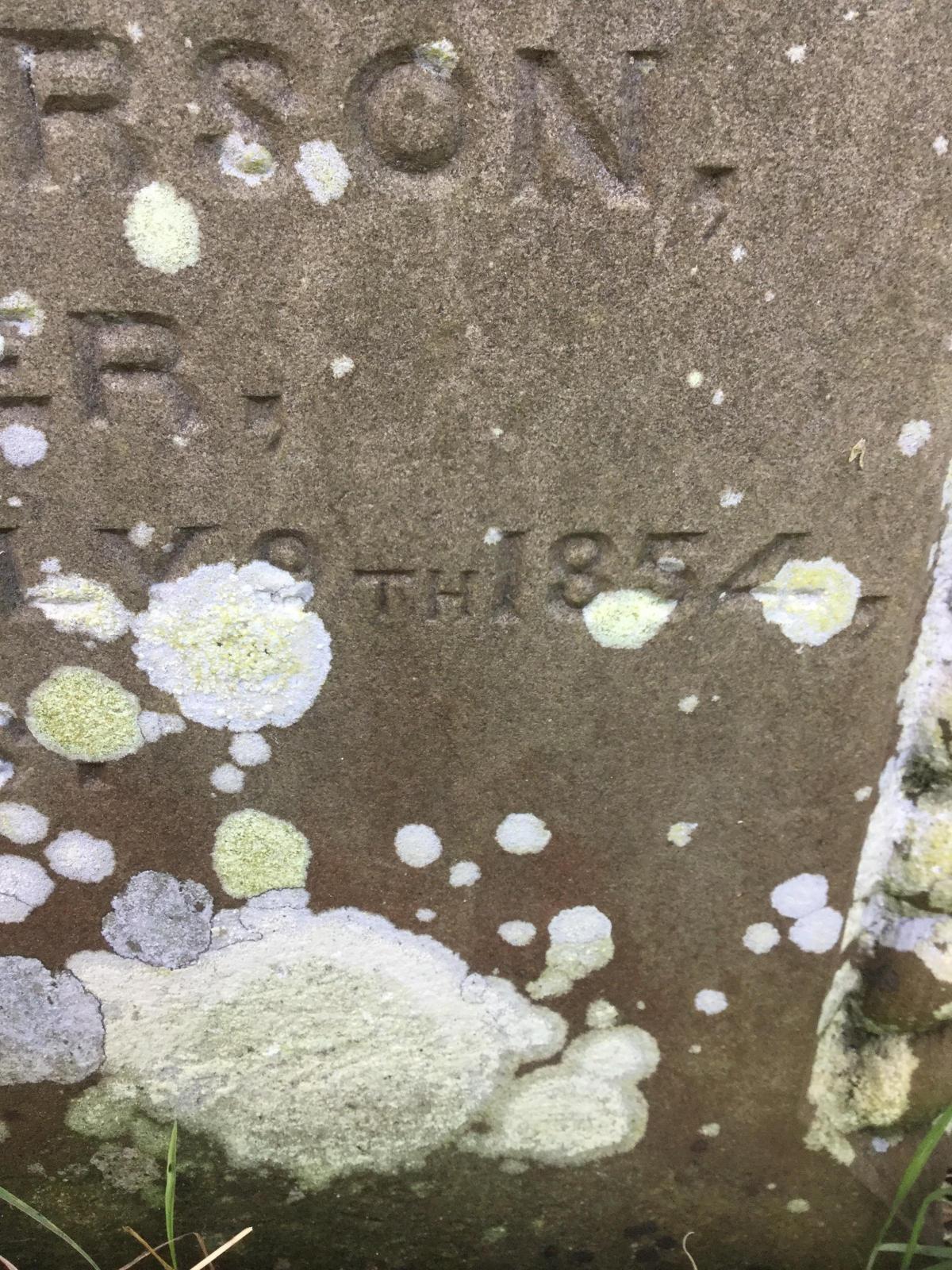

One of the best places to observe a good variety of lichens is a churchyard, especially if a variety of rock types have been used for the gravestones.

The sulfur fire-dot lichen, for instance, only grows on limestone headstones, while the black crottle prefers granite. Probably the most artistic effect is perpetrated by the lemon-coloured rock lichen. It manages to colonise smooth, slate memorials but only on the roughened interiors of the engraved lettering, giving a fetching yellow highlight to the epitaph.

Gravestones almost always bear a date so, if one has never been scrubbed clean during its lifetime, the largest lichens growing on it are likely to be the same age – sometimes hundreds of years old. Using gravestones, lichenologists have estimated that on average lichens in Yorkshire grow a millimetre a year.

This might not seem much but in polar regions growth is even slower with lichens living to an incredible age – some are reckoned to be over 5,000 years old making them some of the oldest living things on the planet.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here