MIKE BAGSHAW, travel and countryside writer, gets captivated by a nature book.

THIS month, I find myself moved to write not about nature directly, but about someone else writing about nature – and doing it rather well.

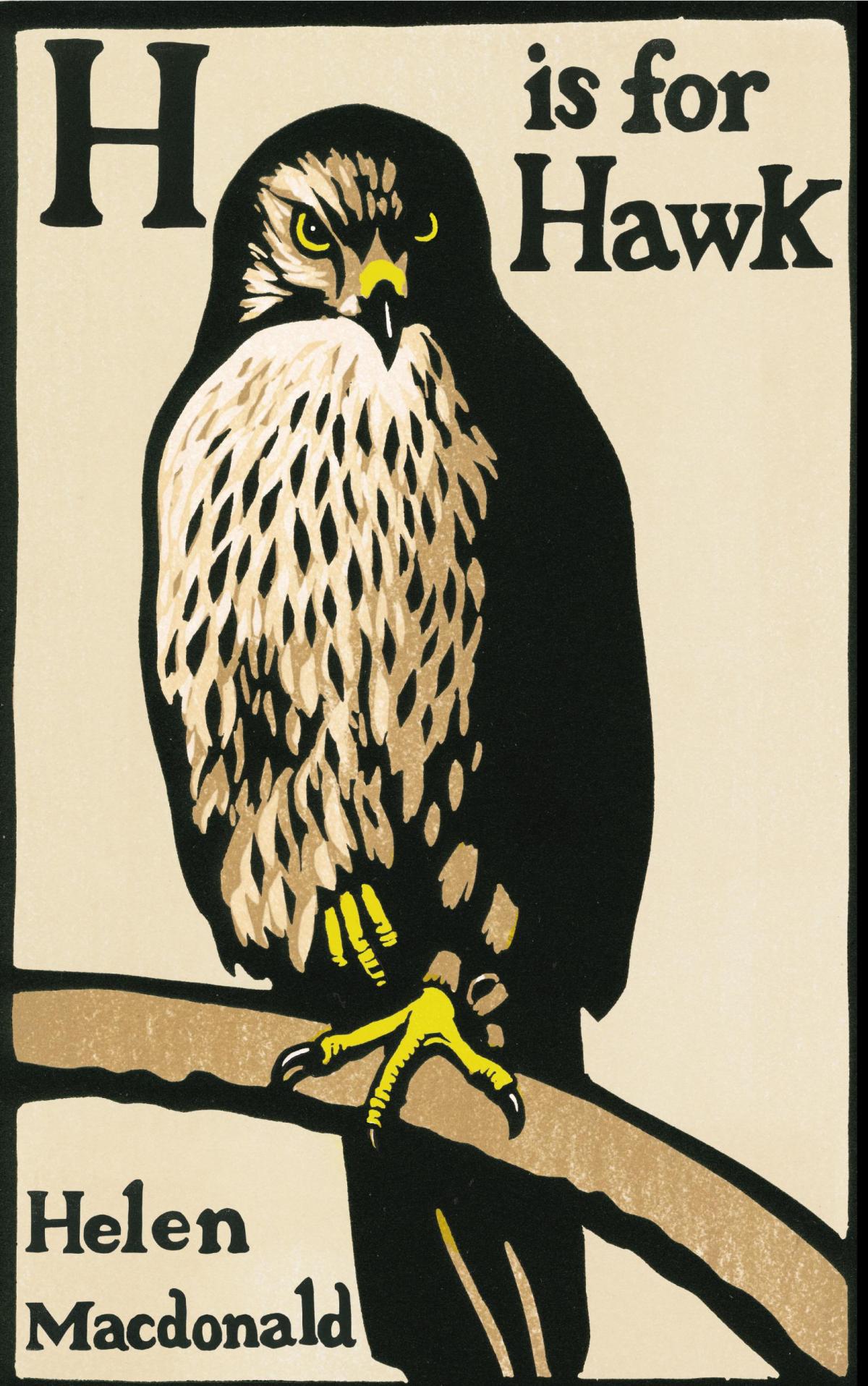

With apologies to Bill Spence and his bookshelf slot, I feel I have to tell anyone who has not heard yet, about a book called H is for Hawk by Helen MacDonald.

It is a biography of sorts – the story of a dark period in Helen’s life after the death of her father. She chooses an odd method of self-therapy, by taking on a young goshawk to train up as a falconer’s bird and the narrative follows the progress of both protagonists.

I was lucky enough to hear Helen herself read extracts from the book at a nature conference in November (newnetworksfornature.org.uk – brilliant by the way).

H is for Hawk had just won the 2014 Samuel Johnson Prize for non-fiction, was soon to be shortlisted for the Costa Biography Award and, as you may have heard on the news last month, won the 2014 Costa Prize for best overall book of the year. If you only read one book in 2015, I can recommend this absolute gem.

The therapeutic value of contact with nature is well known. People swim with dolphins to treat depression and patients in hospital wards recover quicker if they can see trees from their window or hear birdsong.

But there is something about goshawks in particular that seems to inspire a fascination that sometimes borders on obsession?

Helen is not the first writer to attempt an exorcism of personal demons by bonding with a captive goshawk; in H is for Hawk she refers to another book, called simply The Goshawk – penned in the 1930s by a tortured soul named Terence Hanbury White.

T H White is better known as the author of the classic children’s book The Sword in the Stone in which Merlyn the magician turns a young King Arthur into various animals as part of his education.

In one chapter, Arthur spends the night in the hawk house as a falcon unable to sleep for fear of “Cully” the dangerously mad goshawk, a subject the author was very familiar with, having trained his own “insane assassin” as he occasionally called it. It is this wild ferocity, an almost untamable-ness, that fascinates people – that and the goshawks rarity and elusiveness in the wild, in our country at least. As birds of dense, mature woodland, they are very difficult to see.

Consciously avoiding humans is another trait – not surprising considering that they were persecuted to extinction in Britain in the 1800s.

It is only recently that they have made a comeback, a population recovery ironically aided and abetted by escaped falconer’s birds.

Even if they are sighted, identification can also be difficult. A perched goshawk in the distance could pass for a big sparrowhawk and high, soaring goshawks can be a little buzzard-like, but seen close-up there is no mistake.

A hunting goshawk is a thing to behold, radiating power and menace and instilling either blind panic or stunned silence into the rest of the bird population as it rockets through the trees.

Fabulous birds indeed; and guess what – we have them in Ryedale. They definitely breed in the Dalby Forest area and there are probably odd pairs nesting in other forests such as Cropton and Langdale.

A local watching venue with as good a chance as any of giving you a glimpse of goshawks is the raptor viewpoint in Wykeham Forest (signposted from the minor road north of Sawdon).

I’ll be up there in early April when the males make themselves more conspicuous by performing a spectacular courtship display over the tree-tops.

It is all aimed at impressing female goshawks of course, but human observers find it just as entertaining. See you there.

Bill Spence reviews It's Not About the Shark by David Niven>>

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here