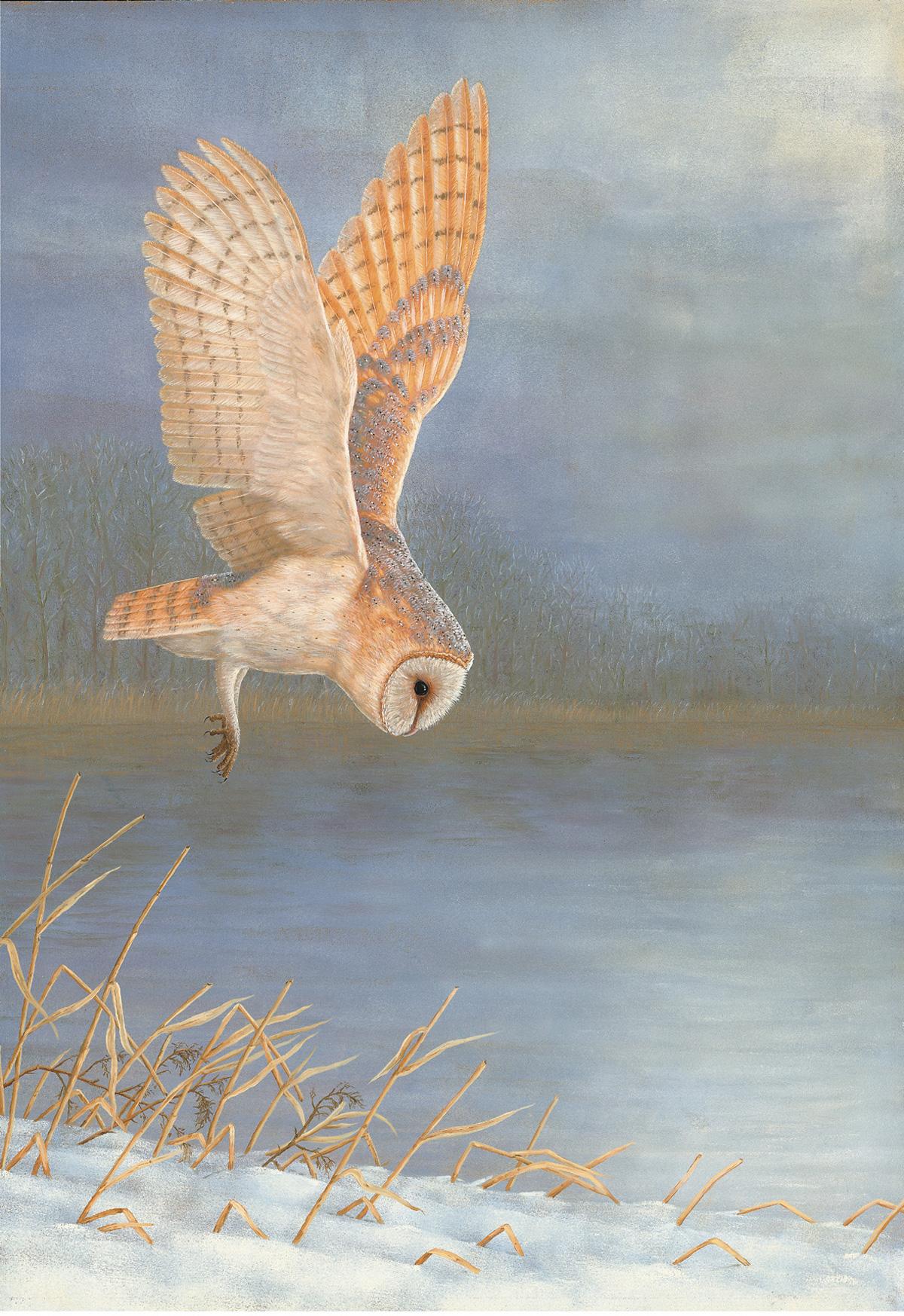

Artist and willdlife expert ROBERT FULLER looks at the reasons why it has been a hard year for breeding barn owls.

AFTER one of the best summers for many years, followed by a mild autumn, my British Trust For Ornithology record sheets monitoring the breeding success of barn owls should have been full this year.

But despite the favourable weather, I had nothing to record. Over the summer I checked barn owl nest boxes that I have put up across the Yorkshire Wolds on an almost weekly basis, but I found no barn owls chicks in my part of the Yorkshire Wolds at all this year.

Barn owls in this region took a drastic hit during the harsh winter of 2010, but they had been making a steady comeback since, and at the start of the year I was particularly hopeful for their future.

So why did this year go so dreadfully wrong? One of the problems was that the summer was preceded by an exceptionally cold spring. We enjoyed such a warm and long summer it is easy to forget that spring was one of the coldest starts to the year I have ever known.

This meant that there was actually no new growth until the end of May and the grasslands on the Yorkshire Wolds remained brown and burned by wind and prolonged frost for far too long for the barn owl’s main source of food, the short-tailed field vole, to thrive.

Barn owls can look quite large in flight but they are mostly made up of feather and weigh a mere 12oz.

To lay a clutch of eggs takes up a huge amount of energy and then the effort needed to dedicate up to five weeks to brooding is a big commitment – and that is even before the owl has to think about finding enough prey to raise its chicks on.

Typically if a female is not in good enough condition, she will not even attempt to breed.

Although my tours of the nest boxes on the Yorkshire Wolds over the summer turned up pairs of barn owls, there were just two apparent attempts at breeding. All one pair had managed was a half-hearted nest scrape in the bottom of the box, while the other pair did actually lay a clutch of eggs but they did not hatch.

I have heard from other barn owl conservationists in the region and the general consensus, despite a few late broods, was that overall it was a very poor year for barn owls.

Everybody loves barn owls and it is easy to get people interested when you talk about how important it is to conserve this beautiful species, but if we are going to achieve this objective what we all need to do is concentrate on the voles that they live off.

These small rodents are far less glamorous and people often don’t see the connection when asked to do their bit for them, but without the voles there will be no barn owls.

There is already a lot of good work taking place to try to restore the rough grasslands that these voles thrive in.

Modern farming methods has meant we have lost 97 per cent of our traditional hay meadows, but here on the Yorkshire Wolds we are lucky enough to have such steep sided valleys that it is too difficult to cultivate.

On much of arable farmland there are now schemes to encourage farmers to leave field margins for rough grasslands and, of course, roadside verges have become a haven for voles in recent times.

Of course, occasionally barn owls can get knocked down by cars as they hunt along these verges, but nevertheless these unspoilt areas are great places for voles.

Unfortunately, however, the fashion for keeping everywhere tidy means that many country lanes have begun to look like neatly cropped lawns. This may look smart to some, but it leaves nowhere for a vole to hide.

There is no point admiring a barn owl if you don’t keep the grasslands for the voles to live in, because without a place for the voles to live there will be no place for the barn owls.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here