DRIVING home late one evening recently, my car headlights picked out a remarkable wildlife display as I wound my way along a narrow country lane in the Howardian Hills.

The air seemed to be filled with the fluttering wings of hundreds of moths – so many that the effect was reminiscent of an un-seasonal flurry of snow. I was immediately reminded of a fabulous book that I read a couple of years ago.

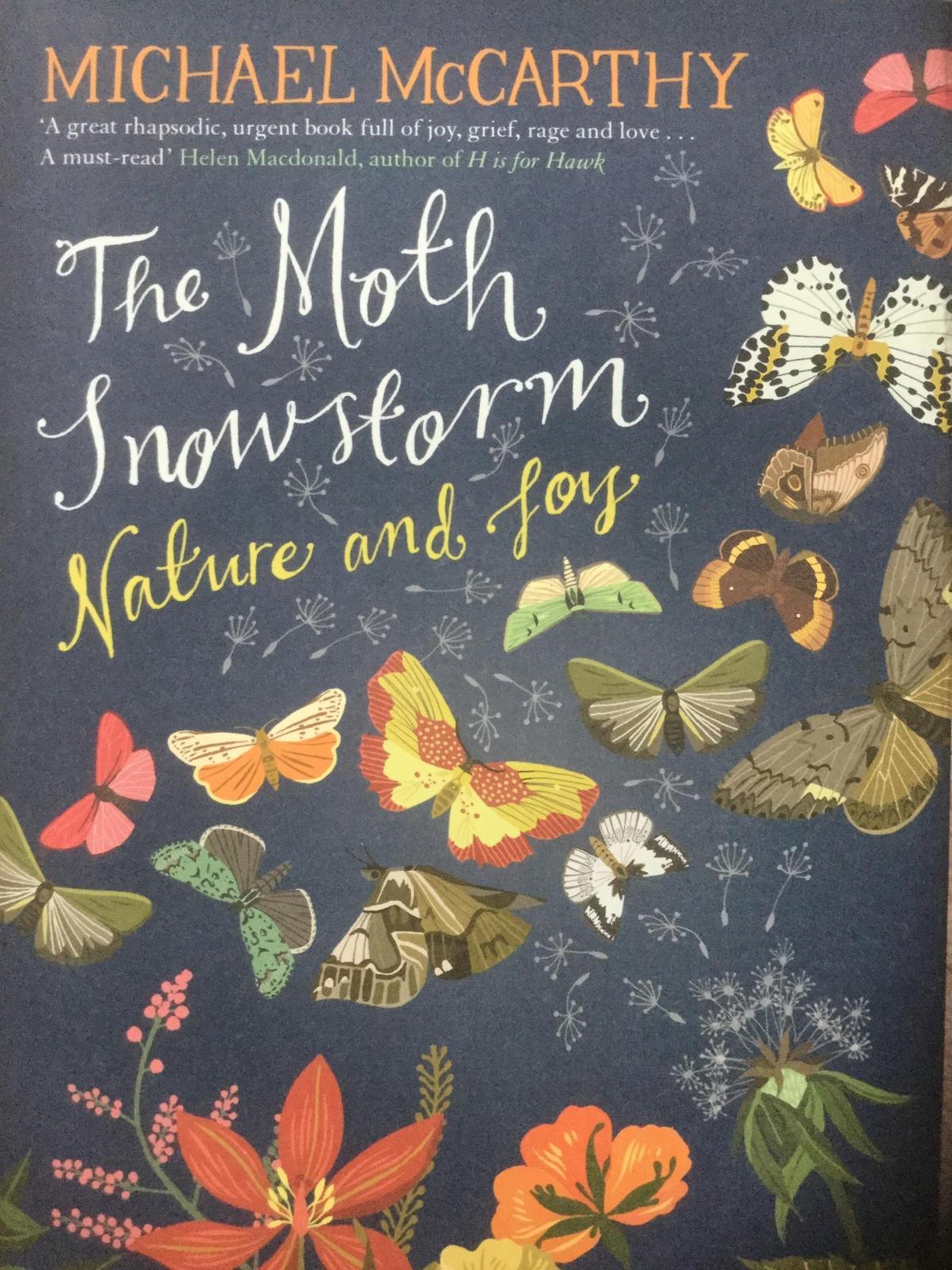

The Moth Snowstorm – Nature and Joy by Michael McCarthy is part biography and part love letter to the British countryside, with the first part of the title referring to the super-abundance of insects in rural England during the author’s childhood years in the 1960s.

The sad fact is that I was able to get so excited by my flurry of hundreds of moths on that country lane when in truth it should have been a blizzard of thousands.

Readers old enough to remember back to the 1960s probably have similar memories to mine of swarms of moths gathering around every street light on warm summer evenings and my dad having to scrape countless other insect bodies from the car windscreen and radiator grill after a drive in the countryside.

So, what has changed? Why are there fewer insects around these days and does it matter? Just for once, the answer to the first part of the question is relatively simple – pesticides, or more specifically, insecticides.

Modern agriculture has become very efficient in producing high crop yields per acre, an obviously desirable situation which has been achieved partly with the help of chemicals designed to kill insects that would otherwise feed on the farmers’ produce.

Unfortunately, these organophosphates, pyrethroids and ryanoids don’t just eradicate their target pests.

Yes, they get rid of aphids from fruit trees, cabbage white caterpillars from brassicas and leatherjackets from cereal crops but they also kill non-pest beetles, ants, bees, grasshoppers, lacewings, butterflies and moths living in field edges and hedgerows.

Some of the more long-lasting chemicals even end up in streams and rivers, killing the nymphs of mayflies, stoneflies, caddisflies and dragonflies.

Overall it is thought that a staggering 75 per cent of European insect biomass has disappeared in the last 25 years.

Now to the second part of the question - does it matter? Unfortunately the answer is a very definite yes. Everything in the natural world is inextricably linked to everything else so if one vital cog is removed or damaged there are inevitable knock-on effects elsewhere.

Insects are an essential food source for almost all larger animals and vital pollinators for most wild and cultivated plants.

Lose our moths and we will lose our bats, lose mayflies and we will lose fish, without gnats, midges and flies most of our songbirds would disappear and as for bees, Albert Einstein famously said, “If bees become extinct then the human race will follow four years later.”

The scientific community is working hard to develop more specific insect control techniques.

Crops can be genetically modified to make them less palatable to certain insects, an early example being potato varieties resistant to Colorado beetle attack.

Another clever strategy is to lace traps with pheromones (species-specific sex hormones) to remove codling moths from fruit orchards, for instance.

Biological control using parasites or predators to attack the pests has also got potential; gardeners and greenhouse horticulturalists have used nematodes and parasitic wasps to reduce leatherjackets and whitefly for years and the wider farming community has learnt from their experiences.

In April of this year the EU officially recognised the severity of the problem and banned the outdoor use of neonicotinoids, a group of insecticides particularly damaging to bees.

Let’s hope that our politicians make decisions post-brexit that will continue to protect our precious Ryedale countryside and allow our farmers access to effective and affordable alternatives. The stakes could hardly be higher.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here