AS December’s floodwaters recede across the north of England, and communities tally up the cost of the devastation that has been left in their wake, a national conversation has been started about how such huge flood events can be prevented in future.

One project that is much-discussed around the country is the Slowing the Flow initiative at Pickering. The project has a real buzz: in January, TV news media descended on the town, and flood experts and politicians proclaimed that more such schemes are needed. Liz Truss, Defra secretary, also name-checked the scheme as best practice earlier this month.

But what exactly is Slowing the Flow, and how does it work?

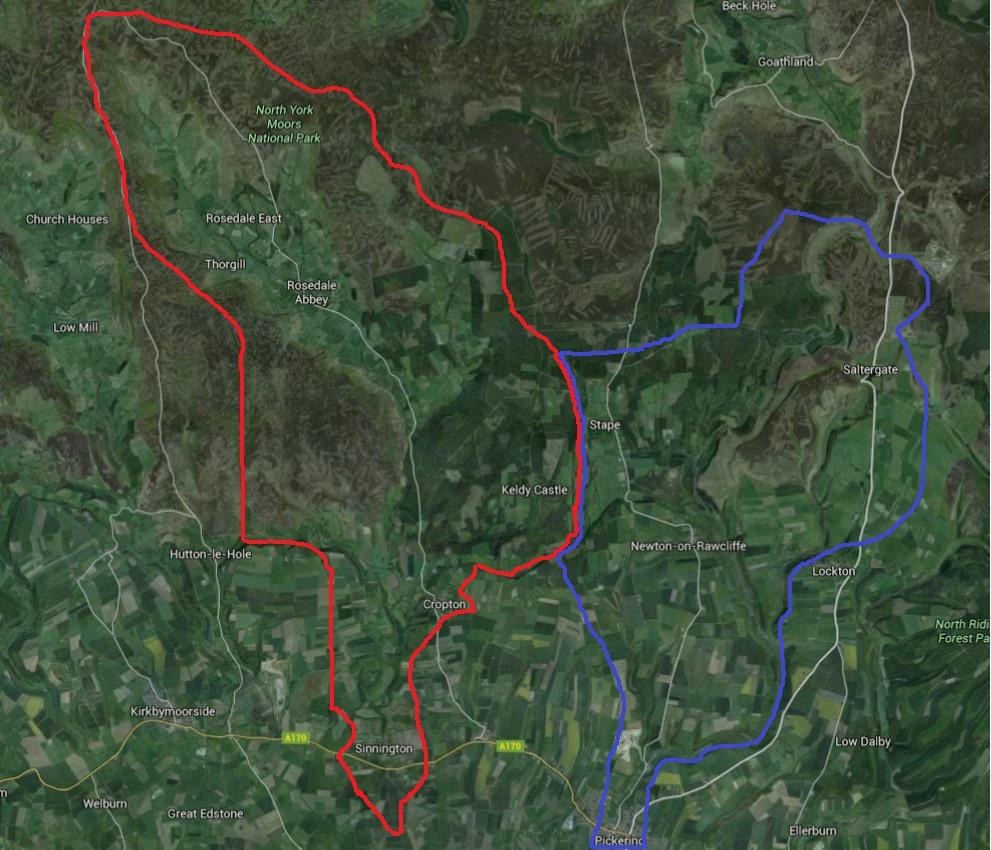

Slowing the Flow was created on a 66 sq km area of land north of Pickering. It is an upland area, partly forested, with a large number of little streams which make up the upper catchment of the river Derwent. The catchment is split into two lung-like halves, each containing a major tributary: the River Seven to the west, and Pickering Beck to the east.

The project was started after four huge flooding events deluged Pickering throughout the 2000s. The last of them, in 2007, caused £7m of damage. In the wider Yorkshire and Humber region, the total damage was estimated at £2.1bn. The community of Pickering initiated a scheme to stop it happening again. Slowing the Flow was born in 2009.

It was a true partnership project, involving Forest Research, the Forestry Commission, the Environment Agency, Natural England, the North York Moors National Park, Durham University and a number of district, town and parish councils. The total cost of the project was about £4m. The broad purpose of the project was to “store” water in the uplands north of Pickering. Most rain and snow falls in the hills, before making its way into rivers and streams, and then surging down into the built-up lowlands. Slowing the Flow was about demonstrating that “integrated land management” is key to reducing flood risks downstream, as opposed to expensive flood walls in towns.

“The more you can do on the wider landscape, with natural processes, the better,” said Phil Roe, area forester with the Forestry Commission.

At the start of the project, the landscape was meticulously modelled. “Modelling is key,” said Mr Roe. “Especially when you’re working on this scale. When the project was first modelled, the results said that we shouldn’t do anything in certain places. Some were too far downstream – you risk double peaks.”

The original aim of the project was to create a large “bund” on the river north of Pickering; effectively a low, recycled earthen dam with a small culvert in it, capable of “holding back” 120,000 m3 of water at peak flow. This water is stored, and then released slowly.

To complement this, project staff aimed to construct two “mini bunds” made of wood, as well as 150 woody debris dams in the forest streams, similar to those that beavers might create, to slow the water down. They also wanted to plant 80 hectares of woodland on the riverbanks and the floodplains, and a further five hectares on surrounding farmland. The trees were largely broadleaf species such as oak.

On top of this, project staff have been trying a raft of small measures on surrounding land such as heather reseeding. Mr Roe said: “It’s quite a holistic approach. You’ve got to look at all aspects that you can. Even looking at run-off from farm roofs and farmyards near watercourses.”

Trees are good at preventing flooding in many ways. They create “hydraulic roughness”, which slows down water flows. They increase water absorption into the soil by as much as 67 times. And if left to its own devices, most of the uplands, which we traditionally have seen as bare and barren, would be naturally tree-covered. The project delivered on all their aims apart from one: they did not manage to plant as many trees as they wanted. Of the mooted 80 hectares, they planted just over half this. The reasons for this shortfall were varied, but key among them was landowners not agreeing to trees being planted on their land. Reasons offered included a desire not to forego income on land, and the lack of a quick return on woodland planting.

At peak flow, the woody dams are estimated to hold back 1,200 m3 of water, the mini bunds 4,000 m3 and the new trees a further 4,000 m3. All this is water that, without these measures, would have flashed into Pickering in a “hydrographic peak”.

“After high rainfall events you look for the signs of where the water got to,” says Mr Roe. “It’s like a tidemark of debris.”

Slowing the Flow has only just finished. Indeed, the groups involved in its delivery haven’t yet had the “wash-up” meeting. Therefore, identifying the bits of it that worked and the bits that didn’t may be tricky. But if the project is deemed successful, what would be the challenges of reproducing it elsewhere?

It will be certainly be harder in treeless landscapes, as they don’t have the ready materials to make the woody dams. And the sheer number of partners and stakeholders presents a logistical problem. “20 people from different organisations in the same room?” said Mr Roe. “It’s always a challenge to get that number of people to a meeting.”

There is a further impact that Slowing the Flow may have on Pickering, and that is on insurance premiums for residents. Forest Research estimate that the flood risk in Pickering has been reduced from a 25 per cent chance in any year to a less than four per cent chance.

Mike Potter, Ryedale councillor and chairman of the Pickering Civic Society, says it is possible premiums will come down in the near future: “The Environment Agency will have to remodel the flood map to reflect the upstream storage,” he said. “This should inform the flood risk maps used by insurers.”

The second phase of the project concluded last summer. Now it’s all about monitoring, maintenance and repair. The project has not entirely eradicated any chance of flooding in Pickering.

“If we get big events there may still be flooding,” said Mr Roe, “just not at the same scale.” Pickering is protected by the bund, but other areas, such as Sinnington, have the natural measures only.

So a widespread collection of low-cost, natural flood defences in the North York Moors are helping protect towns in Ryedale. In the coming months, experts will analyse rainfall levels and hydrographs in the North York Moors from December. This will help them determine just to what extent these measures had an impact here, as towns and cities across the north were submerged.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here