York author Matt Haig will talk openly about his battle with depression at this month’s York Literature Festival. He spoke to STEPHEN LEWIS.

WHEN he was 24, Matt Haig very nearly killed himself.

He was living in Ibiza with his girlfriend (now wife) Andrea. Not in the touristy bit, but in a friend's villa on the island's quiet east coast. It was September 1999, the summer coming to an end, and he and Andrea were preparing to return to 'real life' back in the UK.

He remembers precisely the moment it happened: he's written about it in a blog for a national newspaper.

"It started with a thought: something was going wrong," he wrote. "And then, a second later, my brain started to have something pumped into it from the inside. And then my heart started to go. And then I started to go..."

The villa was on the edge of a cliff overlooking the Mediterranean. He walked out to look at the sea, and at the rugged limestone coastline dotted with deserted beaches.

"The villa... was behind me and, in front, was the Mediterranean, looking like a turquoise tablecloth scattered with tiny diamonds," he wrote.

"And yet, the most glorious view in the world could not stop me from wanting to kill myself. I was going to do it even while Andrea was in the villa behind, oblivious.

"I was walking, counting my steps, then losing count, my mind all over the place. 'Don't chicken out', I told myself.

"I made it to the cliff edge. I could stop this terrible feeling by simply taking another step. It was so preposterously easy – a single step versus the pain of being alive."

He never took that step. Partly, it was fear that stayed him. "The weird thing about depression is that even though you might have suicidal thoughts, the terror of death remains the same," he wrote.

Partly it was the knowledge that he had four people who loved him: Andrea, his parents, his sister. He wished, in that moment when he tried to end his life, that he didn't have them. But he did.

He was also worried that if he did jump, he might not die – but simply be paralysed and trapped forever. So he turned back to the villa, and was sick from the stress of it all.

That was more than 15 years ago. Back in the UK, Matt was initially diagnosed with panic disorder: a condition, he says, in which you are "constantly panicking about panicking". That diagnosis was later revised to one of clinical depression and anxiety.

Three years of depression followed: years of panic and despair in which even walking to the corner shop without collapsing was a daily battle.

People talk about feeling depressed, but unless you've experienced clinical depression you have no understanding of how it feels, he says.

It is like when, sometimes, as lunchtime approaches, people say 'I'm starving'. The difference between that feeling of being a bit peckish, and being really starving, is the same as the gulf between people saying they feel a bit depressed and really suffering from an episode of clinical depression, he says.

He remembers an overwhelming sense of dread. "It was mainly a feeling of being totally trapped: a claustrophobic feeling, of intense anxiety and despair." He felt, he says, like an alien.

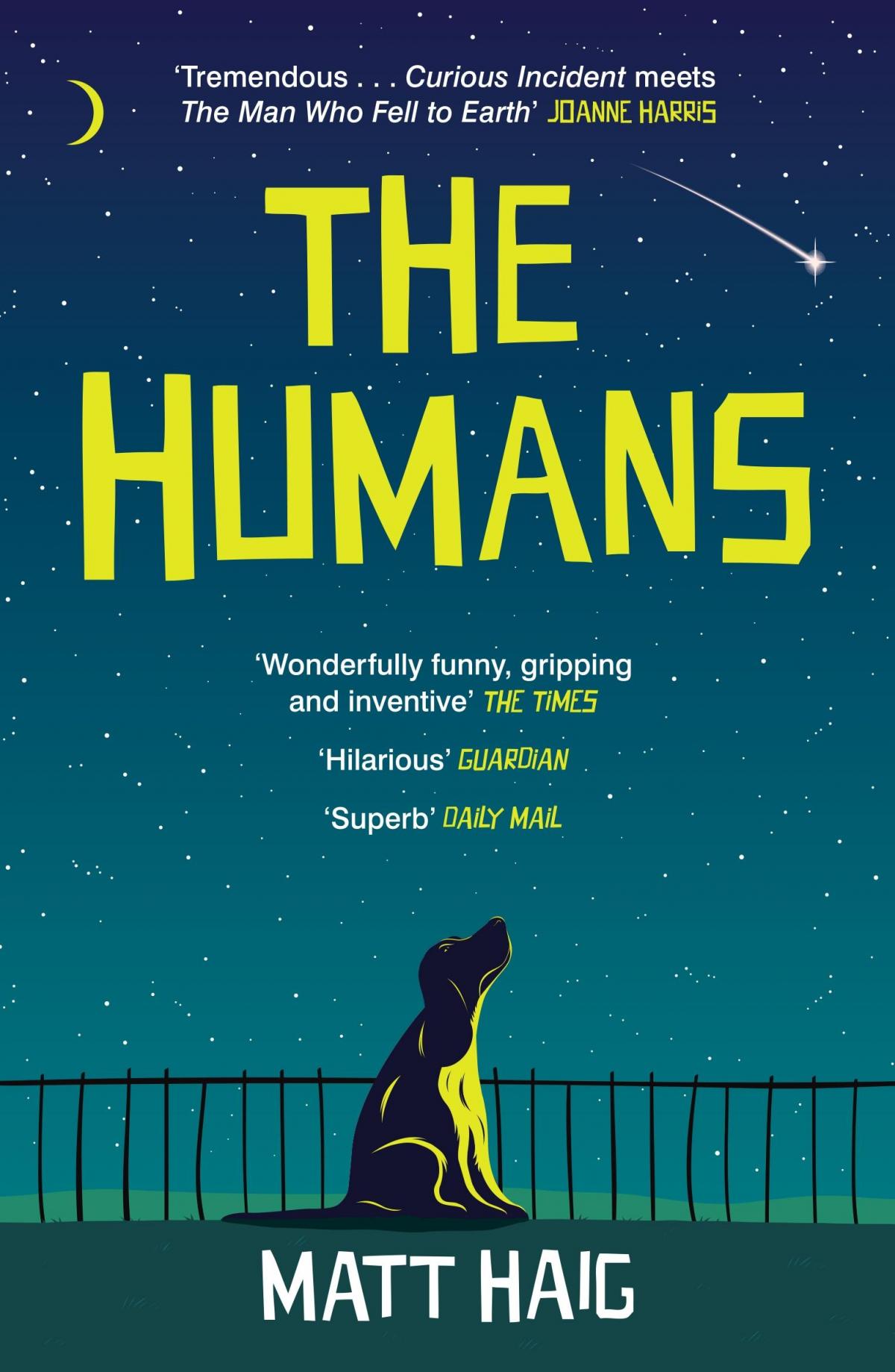

That's interesting. A couple of year ago, he published a wonderfully moving, tragicomic novel, The Humans, in which an alien was sent to Earth to see whether human beings were fit to be allowed to go on living.

The alien takes over the body of a Cambridge mathematics professor – from inside which he observes, with horror and bewilderment, the strange behaviour of these primitive, two-legged creatures.

Gradually, though, the alien comes to understand the humans he finds himself among and even to love them. The book ends with a list of all the reasons why humans are worth preserving.

And yes, Matt admits, speaking from his York home, The Humans really was about him putting, into fictional form, his own battle with depression and alienation, and the process of learning to love life and his own humanity again.

Now he has come out from the shadows and has written, very openly, a book about depression and how to get through it.

It is called 'Reasons To Stay Alive' and that is what it is. It is essentially a note written to his own 24-year-old self.

He is 39 now, married to Andrea, with two young children and a string of bestselling novels behind him. He describes himself as a 'happy depressive': a bit like a sober alcoholic. Depression will always be there somewhere, lurking. But it has lost its power over him, he says.

The first time it struck, quite suddenly, he couldn't see any way through. But now, he knows that when depression tells him life isn't worth living, it is lying. "I know the things it tells you aren't true."

Reasons To Stay Alive is about why he's glad he didn't kill himself all those years ago: and what he would have tried to say to that long-ago Matt to try to break through to him.

It is written with his trademark lightness of touch. Yes, it is dealing with a weighty, serious subject, he says. "But I did not want to write a book about depression that was depressing."

Matt will be talking about his book in public, on March 23, when he gives a talk at Waterstones as part of this year's York Literature Festival.

Actually, he finds it easier to write about depression than talk about it, he says. But he has been doing a lot of talking recently – including with Simon Mayo on BBC Radio 2 – and he has found the warmth of the response hugely encouraging.

"And it will be really nice to give the talk in York, where I live. There will hopefully be a lot of familiar faces."

* Matt Haig: Reasons To Stay Alive, York Literature Festival, 7pm, March 23, Waterstones, Coney Street, York. The book Reasons To Stay Alive by Matt Haig is published by Canongate, priced £9.99.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel