IT’S inconceivable to think that Robin Butler could have been anything other than a smithy; blacksmithing is in his blood.

Not only has this 80-year old been welding, modelling, hammering and shaping metal for more than 45 years, but his uncle and great-grandfather were blacksmiths, too, and he has traced this link back to 1851, when members of his family forged in the East Riding of Yorkshire.

For many years, Robin, who was born in Hull but has lived in Kirkbymoorside since he was four months old, worked for several local firms, where he learnt his trade.

And he really has done his bit to keep this ancient rural art alive and burning bright in Ryedale.

Robin started his career at Russell’s Agricultural Engineers as a welder, and then went to work at Kirk Forge in Kirkbymoorside, where Wilf Dowson took him on as his first apprentice.

“My friend and I went at night to help Wilf set up the blacksmith’s shop, he took me on and it all went from there,” remembers Robin.

Robin stayed at Kirk Forge for more than 25 years and after that went back to Russell’s to work in the welding machine shop, where he remained for 15 years, then to Micro Metalsmiths, where he stayed for the next 12 years.

It was during his time at Wilf Dowson’s that Robin undertook some of the most prestigious jobs in his career, including the intricate alter rails at St Wilfrid’s Church in York, which he worked on in 1948; and the Rados Screen in York Minster.

“This was commissioned by the international Masons and looked enormous in the workshop, but when it was put up in the Minster it didn’t look so big,” smiles Robin.

He also worked on repairing the Satyr Gate at Castle Howard as well as a number of gates at Harewood House near Leeds, plus the railings of the memorial chapel to King George VI in St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle, and on many prestigious metal works in many churches and universities around the country, notably on those designed by architect George Pace in the 1960s.

“I worked on a lot of George Pace’s work and was very pleased with some of that, as it was modernistic and symbolic work, which I really enjoyed doing,” said Robin in his strong, warm Yorkshire burr.

Yet, though he is very proud of what he has achieved in his ‘professional’ life, it is the work that he does and has done at Ryedale Folk Museum in Hutton-le-Hole that has held such a very special place in his life.

Robin has been involved with Ryedale Folk Museum since its inception and, according to its current director, Mike Benson, “Robin is the museum”.

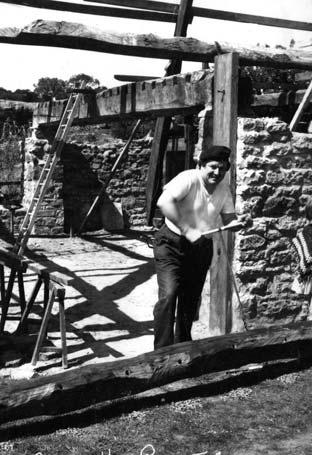

He become involved as a volunteer in the museum in 1964, when Raymond Hayes, Burt Frank and Wilf Crosland came up with the idea of a historical village within a village, and has been involved in many notable developments and discoveries there since, including dismantling buildings and re-building them, notably Harome Manor House in 1972, during which time he made a hugely significant historical find.

“It was when we were pulling down the thatching from the manor house that I found a blackened spoon,”

recalls Robin, who has a remarkable memory.

“It turned out that it was a silver spoon dating from around 1510 which was the oldest spoon to be found in England at this time – it went to Treasure Trove in 1976 and I received the reward, which was, if I remember correctly, £1,362.

It’s thought that it was put there for safekeeping by a soldier who went off to fight for his lord, or perhaps a servant who had stolen it. It was in all the national news and the British Museum even made a replica of it.”

He was also involved with transportation to the museum of an Elizabethan glass kiln unearthed near Rosedale, and it remains in the museum to this day, although was damaged during this winter’s severe weather.

As well as all of this, Robin has been blacksmithing in his workshop at Ryedale Folk Museum since the mid-1960s, and has made nails for visitors which have found their way around the world, as far as China, Brazil, Australia and New Zealand, and for famous guests such as Prince Andrew, TV presenter Anneka Rice and actor Kenneth Cope.

However, Robin is far from retiring and leaving this family tradition of blacksmithing behind, as he still regularly demonstrates this skill in the blacksmith’s shop at the museum, often for school parties and the general public Ryedale Folk Museum has paid a huge part in Robin’s life, as his late wife, Edith, who was born and bred in Hutton-le-Hole, also volunteered there, and he goes there regularly whenever he feels like it.

He is so much a part of the museum’s family, that they organised a surprise 80th birthday party for him in March.

“They really did me proud,” he smiles. “It was fantastic and I couldn’t have wished for a better birthday.

“I’ll continue to go to the museum forever.”

Far from letting this ancient rural art of blacksmithing die out, Robin has encouraged the younger generation to take up the bellows and hammers, and though his two children haven’t followed in his footsteps, he has trained a number of apprentices, including Charlotte Bramley.

“I gave Charlotte her first lesson in blacksmithing back in 2005 when she was 16, when Mike Benson, the director of the museum, asked me to and at first I thought, ‘women want to be everywhere, is there no sacred place left for a man?’,” chuckles Robin.

“But she had her lesson and is a natural and is now at Hereford School of Practical Blacksmithing, where she went straight into year two and she’s top of her class.”

Robin is also very active in his local community and is a founder member of Kirkbymoorside’s History Society and camera club, of which he is a life member, and he is also a life member of the town’s Family History Group.

It’s fair to say that Robin has made his mark on many places as well as on the lives of many people through his work and the museum is soon to publish a hardback book of his memoirs.

“When I look back, I’ve had an interesting life and have done a lot of things,” he said, “and, because of the museum, I have had the opportunity to do so many things I would otherwise have not been able to do.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here