Sepia photos from the western front may sum up the First World War but, as an exhibition at Castle Howard shows, documents give us a snapshot of the home front - the other half of the Great War story. MATT CLARK reports.

FOR the first 20 years of his life James Prest led an idyllic existence. Born in Coneythorpe he went on to work at his family farm on the Castle Howard estate, spending carefree summers mowing hay.

Then in came the First World War and out went the lights across Europe.

As a farm worker James was initially required to stay at home, but in 1916 he enlisted in the Durham Light Infantry.

Just over a year later, those halcyon days spent in North Yorkshire seemed an eternity away. James had become a prisoner of war; an emaciated figure forced to work in enemy occupied Belgium.

Like many veterans he refused to talk about those wartime experiences, but when he died James's family discovered his prison camp diary.

Today the booklet is on display in the 'big house' up the road' , revealing its secrets as part of Duty Calls; Castle Howard in the time of war.

But as curator Dr Chris Ridgway explains, the conflict didn't just affect estate workers.

"The stories are told in a sequence of panels accompanied by photos, documents and artefacts relating to each panel," he says. "The main one concerns Michael Howard who was killed at Passchendaele."

Michael was an adventurer and had already seen action during the Boer War. A restless soul, he later wandered the world until he ended up in Canada.

When the Great War broke out he rejoined his old regiment and served in France until his death in 1917.

The exhibition reveals two conflicting accounts about how Michael was killed. His family had believed it was from a sniper's bullet, but another transcript has come to light that describes how he volunteered to crawl into no-man's land to cut some barbed wire.

The account goes on to say Michael was with his platoon when it advanced, but he was never seen again.

Sepia pictures aside, the most absorbing things in Duty Calls are documents. Dr Ridgway says many may seem dull as ditch water at first, but they reveal a day to day account of how the estate was run; a snapshot of the home front - the other half of the Great War story.

"It's mainly a document led exhibition and I quite like to call it 'oh what a regulatory war'." says Dr Ridgway.

"It's only when you see these forms that you realise how regulated people's lives were; how the state interfered and demanded information about them."

In a nutshell; what seemed normal in 1914 was no longer the case in 1916.

Like all country houses, Castle Howard was deluged with official communications and Charles Luckhurst, the resident agent, was responsible for dealing with most of them. Filling in censuses, appealing against estate workers being called up; that sort of thing. The minutiae of life.

"There is this whole issue of exemptions for occupations; people who didn't have to be conscripted." says Dr Ridgway. "We have a whole mass of forms and in most cases they have been filled in, so we have names and personal particulars."

And he hopes that may spark a flood of hitherto hidden stories.

Dr Ridgway reveals another interesting fact; 40 per cent of men who enlisted were rejected on medical grounds. With the military requiring more and more men, conscription was introduced to address the shortfall from voluntary enlistment.

But who would be left to grow the food? Especially after 1917 when Lloyd George announced 'The British farmer will defeat the German submarine.'

Grassland was turned over to food production, but with fewer hands to work those extra acres and fewer horses, because they too were commandeered to the front, estates like Castle Howard found it increasingly difficult to function.

Dr Ridgway explains that agriculture was supposed to be an exempted industry and his exhibition refers to Luckhurst's official pamphlet that advised which sectors applied.

But at times the booklet didn't help at all. It seems the occupation was exempt, not the man and the military pushed for it to be filled by someone who had failed his medical, however unsuited he may be to the role.

"This is a document led exhibition, it's not big on objects," says Dr Ridgway. "But it does go to the heart of how an estate works.

"Perhaps more interesting is the German prisoner of war camp established in Welburn in 1918. That was one solution to the shortages of manpower."

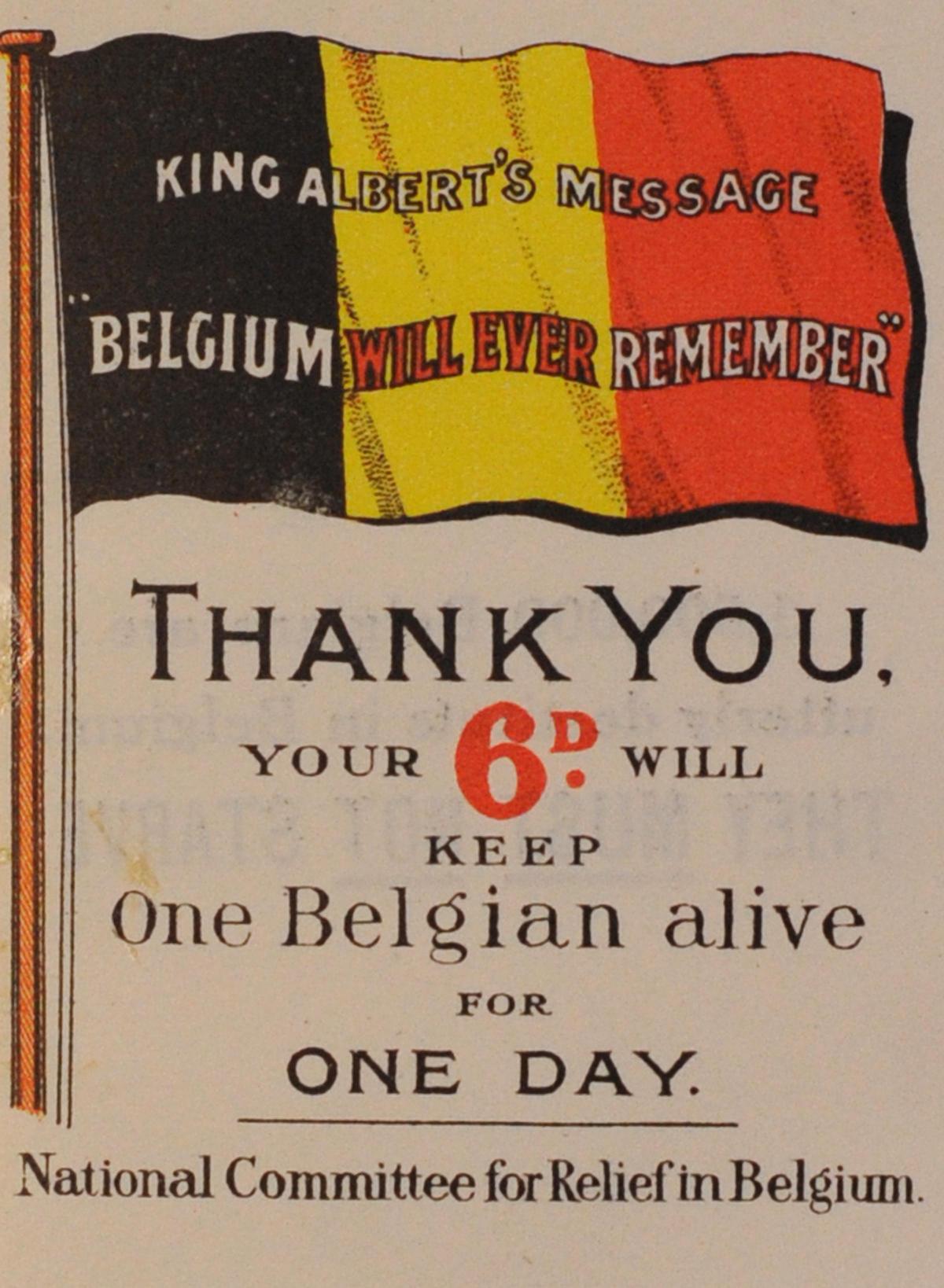

Another, told in the exhibition, is how 60 Belgian families helped at the estate.

But there are too many manuscripts and booklets to put on show, so, to accommodate them all, Dr Ridgway has decided to write a book to accompany the exhibition.

He hopes it will also help to unearth similar stories that have been languishing in sideboards for almost 100 years.

"I didn't find any of this stuff in the exhibition until I started looking at this period of Castle Howard's archives," says Dr Ridgway. "There must be lots more out there and if we need to produce a second or third edition that's fine."

After all, he does have four years until the centenary of the war's end.

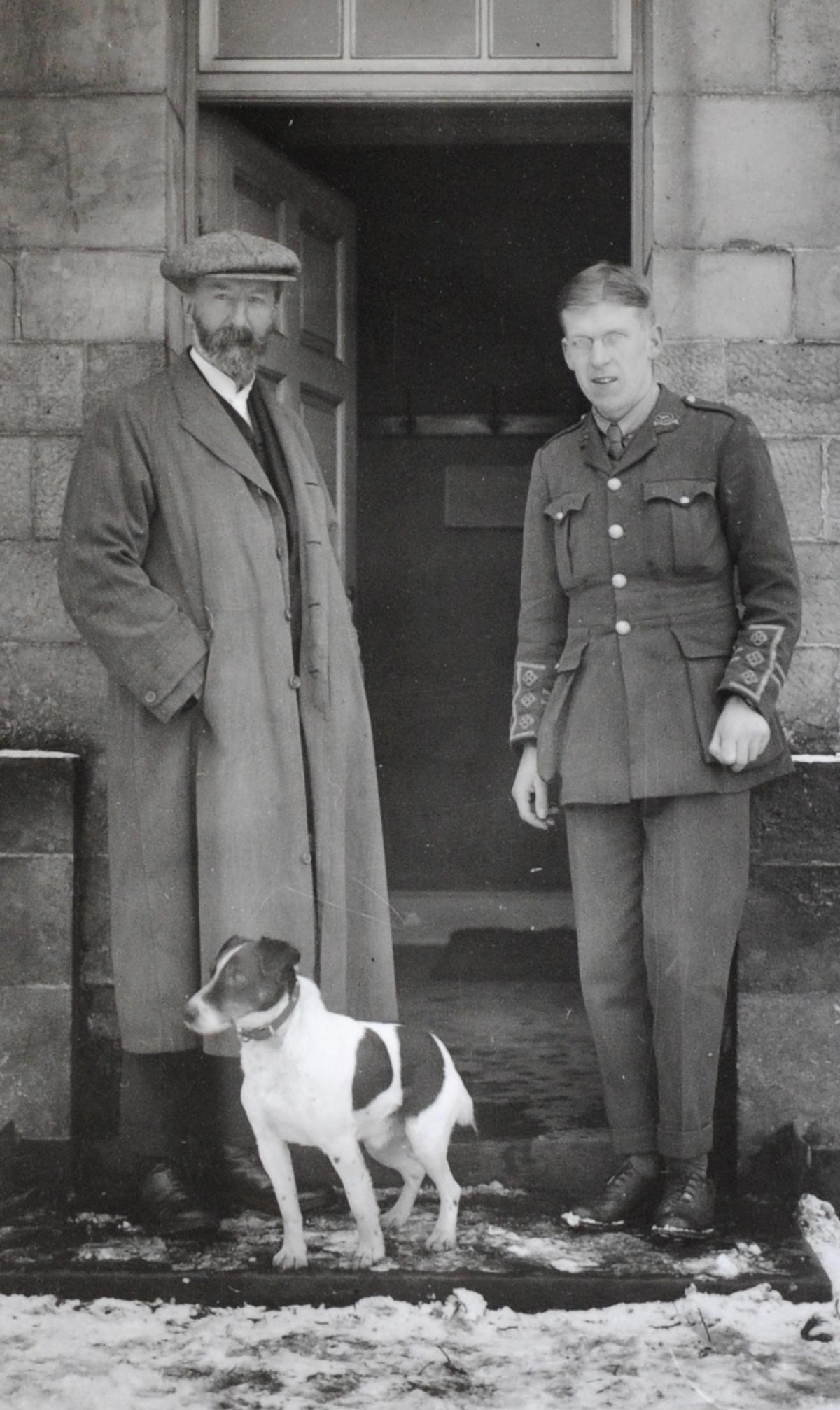

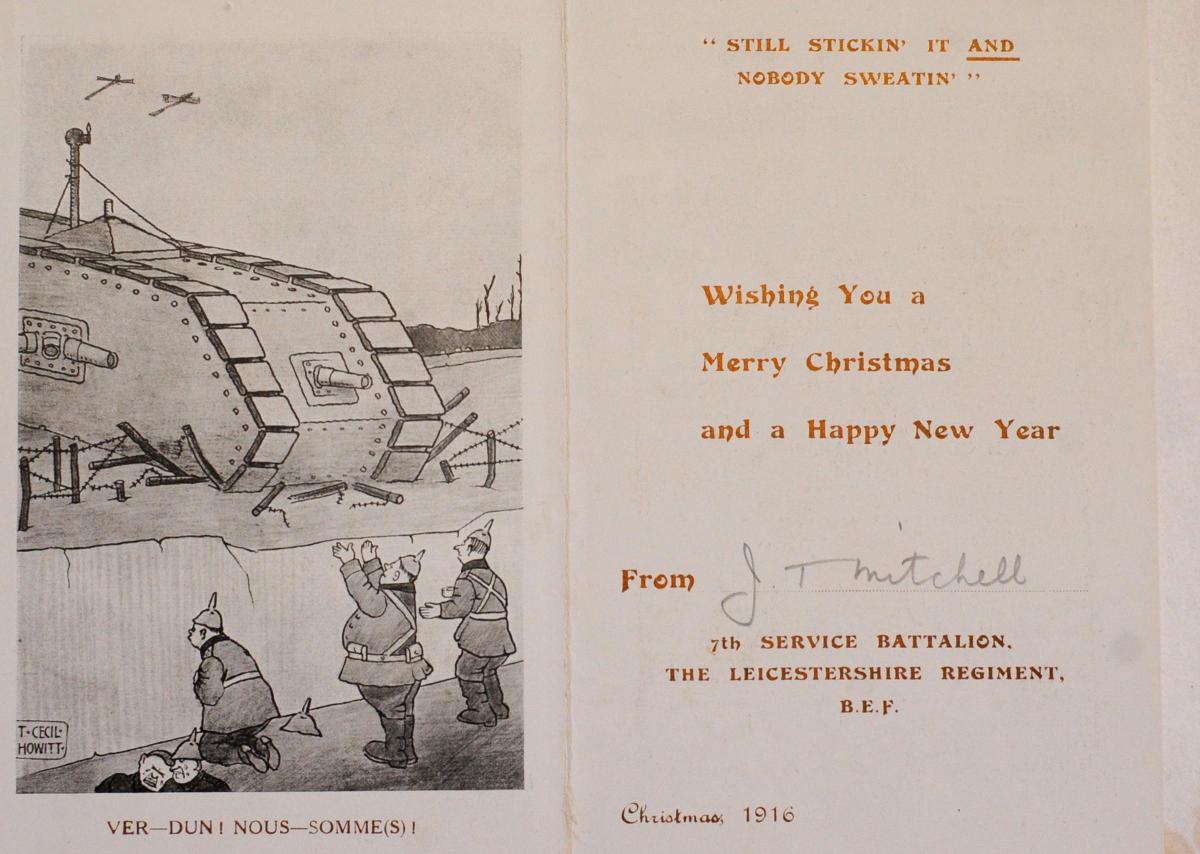

One thing the archives had failed to yield was a picture of Luckhurst. Nor one of James Mitchell, Rosalind's adopted son. Until recently the prize exhibits for his story were a Christmas card he sent home from the front and a poignant personal effects list detailing his five pairs of spectacles - one damaged.

Then, in an incredible stroke of luck, Dr Ridgway was one day rummaging in the archive, when he happened upon some glass negatives.

One of them depicted both Luckhurst and Mitchell.

"It was serendipity really and at enormous cost the negative produced a rather nice image.

"It shows Mitchell as hardly warrior caste, but he took to military life well and was an acting Captain by the time he was killed."

Dr Ridgway says pictures of the Howard's were far easier to find and Duty Calls reveals some interesting insights into their thoughts about the Great War.

"The family were strong Liberals. They liked Sir Edward Grey and Asquith, but detested Lloyd George. They thought he was devious."

Another panel suggests that Countess Rosalind Howard wasn't too keen on the military either.

When the Lord Lieutenant wanted to requisition Castle Howard for his Divisional HQ, she went through the roof. "I don't want them swarming about the house and park," Rosalind wrote. "Let them go to the Fevershams or the Middletons or to Hovingham."

Her son Geoffrey , who was a serving MP, was clearly embarrassed by this intransigence and to signal his support for the military, wrote home saying he had taken a commission and was going to France.

Rosalind remained unconvinced, however, and instead supported the war effort by accommodating homeless Belgian families.

She might have been opposed to the Army, but Rosalind was more than happy to welcome the police. And with good reason. Castle Howard was under threat from suffragette activists and placed under special protection measures.

Which was rather ironic, because for decades Rosalind had campaigned for women to have the vote.

Family and worker's stories aside, Dr Ridgway has also included some generic First World War artefacts in Duty Calls, such as copies of Punch - the staple of country house life - and Struwwelpeter (shock-headed Peter), a19th century German book of cautionary tales for children.

There is also a copy of the 1914 English rewrite entitled Swollen Headed William, after Kaiser Wilhelm, in which he is portrayed as the baddie and Kitchener the goodie.

Alongside this wealth of First World War poignancy, is a timeline of family tragedy, beginning with John Howard's death at Bosworth Field, while fighting for Richard III, and the King's exhumation in Leicester 530 years later.

In between it illustrates how often the Howard family lost its sons to war and how much it has served the country at prayer and in government. Half a millennium of answering when duty called.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel